On Sunday afternoon we were in the car on the way to his step-dad’s birthday, and Fletcher was wearing Dad’s shirt.

“You hate this shirt don’t you?” Fletcher had said an hour earlier when he put it on, because he saw me looking.

“No no it isn’t that.”

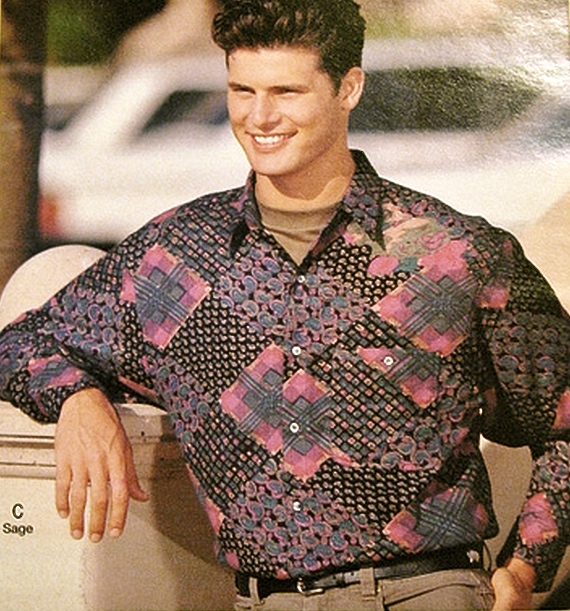

The shirt is hideous, it’s this weird pattern of purple and black blobs.

“Dad, really?” I used to say, lifting an eyebrow, when he wore it.

“What?” Dad would say, with his little smile. He had gotten the shirt in the early ’90s, still in the holdover influence from the ’80s, from a store called “Structure,” which no longer exists. And often he wore it with pleated black khakis and these leather square-toed sneaker-like shoes, which sort of looked like bowling shoes, for an overall goofy-white-guy ensemble that he only could have improved with a gold chain necklace as the finishing detail.

And the shirt is in mint condition, as if Fletcher just borrowed it right from Dad’s closet. As if Dad himself might have worn it lately. For all these years Mom saved it down in the basement thinking my cousin might want it, and then, all of a sudden, she pulled it out and gave it to Fletcher instead.

And now Fletcher was wearing it as we drove to his step-dad’s birthday, and as Bob Marley’s “Could You Be Loved” played on the stereo.

Dark curls of chest hair showed in the place where he’d left the top button undone. I had a sideways glance at him while he stared straight ahead, watching the road.

Could you be love and be loved?

Could you be love, wo now! – and be loved?

The same was true when Dad wore it: A tuft of chest hair showed overtop the V where he left a button unclasped. And at the underarm seams there would have been the very faint trace of Dad’s prickly man sweat.

The road of life is rocky and you may stumble too,

So while you point your fingers someone else is judging you

I’d been seeing Fletcher maybe three or four months when he hung his sweaty bike clothes on the little drying rack in my bathroom – this is years ago now – and afterward I went in and the scent of prickly man sweat had filled the air of that dingy yellow-brown tiled galley.

And I stood there and took a long deep nasal inhale.

You ain’t gonna miss your water until your well runs dry

In the basement Dad used to hang his sweaty tennis clothes on a makeshift clothesline. When I went down there the warm humid scent hung on my skin and prickled my nostrils.

I had found it repulsive, at the time.

Just like this shirt, this hideous shirt, which I now stared at, as we drove. There were green blobs mixed in with the purple and black, and tortoise shell buttons.

Though the tuft of chest hair would be mostly grey now, if it were Dad’s.

He would have attached a delicate set of clip-on shades to his eyeglasses, for driving, and just now he would be looking out at the road with all his focus and attention.

“It’s the shirt isn’t it,” Fletcher said, glancing at me. “You hate it.”

“No no I don’t hate it,” I said.

Could you be – could you be love?

Say something! Say something!

Could you be – could you be – could you be love?

“Not at all.”